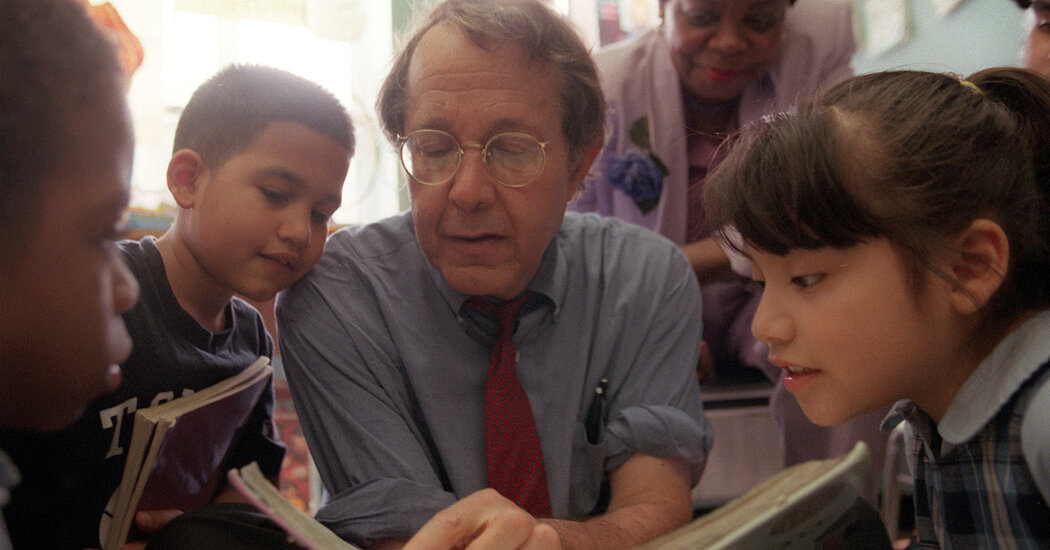

There are some causes in Jonathan Kozol's half-century of writing about America's failure to correctly educate poor black and Hispanic youngsters, which started with “Dying at an Early Age,” a blistering account of the his yr of instructing within the Boston Public Faculties.

Decrepit faculty buildings with rancid loos and leaking ceilings. College students stultified by scripted curricula and infinite check preparation. Desolate city neighborhoods with uncared for parks, crumbling residences and worn-out, underpaid lecturers. Desperation is punctuated by vibrant and vigorous youngsters, who little doubt discover the plain injustice that adults have been educated to miss.

“Dying at an Early Age,” revealed in 1967, turned him into the form of broadly learn public mental that not exists.

Now, at 87, he has revealed “An Finish to Inequality,” his fifteenth e-book — and his final, he says. It’s an unapologetic cri de coeur concerning the failings of colleges serving poor Black and Hispanic youngsters, and thus, the nation's ethical failure to finish the inequality it has documented for many years.

Critics have lengthy mentioned that Mr. Kozol has centered an excessive amount of on all the things that’s flawed with American public colleges, and never sufficient on fashions for achievement. They level to constitution colleges, charismatic principals and early studying applications driving change, even in some deeply segregated neighborhoods.

However Mr. Kozol characterizes these as marginal reforms supposed to plug right into a system that’s unequal by design. And in his lengthy profession, he has seen a long time of nationwide reform efforts — “A Nation at Danger,” No Youngster Left Behind, Race to the Prime, Each Pupil Succeeds — come and go, whereas some points stay a lot the identical.

Academic alternative continues to be largely divided by the power of oldsters to pay for housing in desired ZIP codes. Some growing older faculty buildings are nonetheless stuffed with lead. Black and Latino college students are nonetheless disproportionately subjected to harsh types of self-discipline: silent hallways, remoted lockers, even bodily restraints.

“I don't have compelled optimism proper now,” Mr. Kozol mentioned in an interview. “If we're speaking about black and Latino youngsters in our public colleges, I believe it's unrealistic to be optimistic.”

He was talking from an armchair in the lounge of his canary yellow colonial home in Cambridge, Mass., the place he lives alone, helped by a number of younger assistants. He was briefly married and divorced within the Seventies and had no youngsters, devoting years to immersive reporting. He spent his days in colleges and homeless shelters, and wrote by hand within the late evenings — nonetheless his favourite time to work, he mentioned, whereas sipping an iced espresso at nightfall.

The room was stuffed with teddy bears – he began gathering them when he was too infirm to take care of canine – and previous problems with left-wing magazines like The Nation and The Progressive. A close-by espresso desk was piled excessive with memorabilia, organized for a possible acquisition, Mr. Kozol mentioned, of his papers by the New York Public Library.

It included a signed {photograph} of Langston Hughes, which the poet despatched in 1965, after Mr. Kozol, then 28, was fired for instructing a principally black fourth-grade class the poem of Mr. Hughes' “Ballad of the Landlord” — then thought-about a subversive work by the directors of Boston.

In “An Finish to Inequality,” Mr. Kozol makes use of daring language to make his case.

He rejects the thought, well-liked in some academic circles, that specializing in the issues of racially segregated public colleges is encouraging a form of deficit mentality, by which black, Latino and Native American youngsters are thought-about extra for what they lack than . for what makes them resistant.

“It’s a delicate dilemma,” writes Mr. Kozol. “If we will't speak about victims, if the phrase is out of favor, what different language can be utilized to speak about youngsters who’re confronted with cognitive suppression in nearly each facet of training?”

He continues: “Then once more, if there are not any victims, then no crime has been dedicated. If no crime has been dedicated, there could be no cause to demand reparation for what these youngsters endure of their sequestration colleges. Avoiding a disfavored phrase can’t erase actuality.”

The answer, he argues, continues to be the yellow faculty bus, which transports poor youngsters to alternatives in wealthier neighborhoods and cities, the place they will study alongside upper-middle-class friends and luxuriate in among the benefits that his dad and mom assured him: wealthy arts. applications, international language programs, science labs, vibrant libraries.

The system we’ve got as a substitute is nothing wanting “apartheid”, writes Mr. Kozol. The persistence of lead paint and pipes within the colleges of poor youngsters is “mind genocide,” he provides, and the finances cuts are proof of a “struggle on public colleges.”

Mr. Kozol, who grew up because the son of a physician and a social employee within the prosperous Boston suburb of Newton, credit Archibald MacLeish, the modernist poet who taught him at Harvard, with serving to to develop the his writing type.

“He inspired me to make use of sturdy phrases,” he recalled. “There’s a tendency to imagine that the extremes of expression are at all times flawed, and that the reality, for its personal choice, likes to dwell within the center. It doesn’t at all times dwell within the center.”

After school and a stint as a failed novelist in Paris, Mr. Kozol had deliberate to earn a Ph.D. in literature.

His life modified in 1964, when civil rights activists James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman had been murdered in Mississippi.

“What am I doing right here,” he recalled pondering, “sitting in Cambridge, and speaking concerning the metaphysical poetry of John Donne?”

Quickly after, he taught in Roxbury, a predominantly black neighborhood in Boston, and arranged alongside dad and mom who wished to enroll their youngsters in high-quality colleges, first in Boston and ultimately within the suburbs.

His activism helped set up a volunteer busing program referred to as METCO, which nonetheless exists at present, transporting 3,000 college students a yr from Boston to suburban colleges. Analysis exhibits that college students accepted into this system earn increased check scores and have higher school and profession outcomes than college students who apply to METCO however don’t win a spot within the random lottery.

The large thought in Mr. Kozol's new e-book is a large federal and state funding — “fixes” — to broaden voluntary busing applications like METCO. One other mannequin is voluntary two-way busing, which makes use of themed magnet colleges to draw middle-class college students. to the poorest neighborhoods, opening locations in middle-class colleges for low-income youngsters.

Whereas Mr. Kozol's writing is on no account dry, his information of training analysis has at all times been cautious and rigorous, mentioned Gary Orfield, co-director of The Civil Rights Undertaking on the College. of California, Los Angeles, an institute that gives knowledge on civil rights. persistence of faculty segregation by race and sophistication.

Dr. Orfield credited Mr. Kozol with not permitting himself to be distracted by the sorts of technocratic faculty reforms that politicians usually choose, reminiscent of growing high-stakes checks.

“It's simply relentless,” Dr. Orfield mentioned. “He’s indignant and offended by the truth that he sees forwards and backwards. And nobody cares.”

Mr. Kozol is way from a lone voice in asking the nation to refocus on faculty segregation and inequality between wealthy and poor districts. A number of new organizations in Washington are devoted to those points, and have attracted influential supporters.

However Mr. Kozol is upset that mainstream Democrats not often assist large investments at school desegregation. And he mentioned he's not concerned with different types of faculty selection, reminiscent of charters or vouchers, which additionally assist low-income college students escape underperforming colleges. Like many conventional liberals, he sees these choices as monetary leeches on the general public faculty system, and is skeptical of their assist from Republicans and conservatives.

He started writing “Ending Inequality” earlier than the Covid-19 pandemic, and the e-book barely mentions how the disaster has disrupted training coverage, as colleges within the nation's most liberal cities have been closed the longest, with low-income college students of coloration falling behind as properly. additional again.

Nor does it tackle the truth that after the pandemic, dad and mom — together with a few of those that care most — have turn out to be extra prone to assist faculty selection.

This omission angers some training activists, even those that admire Mr. Kozol.

“You’ll be able to't repair the system that damage the individuals,” mentioned Derrell Bradford, president of 50CAN, a bunch that helps the enlargement of constitution colleges and vouchers. “You need to give to the people who the system has broken.”

However Mr. Kozol sticks to the normal notion of public training – a system for everybody. “A democratic nation must have a really democratic, well-funded public faculty system,” he mentioned.

On a desk subsequent to his armchair was an image body drawing, now pale, of a solar breaking over the horizon. The artist, Pineapple, was a tenacious woman who seems in a lot of her books, chronicling the work of rising up within the South Bronx following the crack epidemic and AIDS.

“I requested her, 'Does the solar rise or set?'” Mr. Kozol recalled. “And he or she checked out me and mentioned, 'You resolve.'